Despite the changes the capital of Costa Rica has experienced over the years, the past still exists within the city. In downtown San José we find impressive older edifications with imposing architecture and exquisite details that tell the story of luxury and lifestyle of its inhabitants in the late 1800’s – a legacy that you can still enjoy today. You just have to learn to feel and explore this small Latin American city that has always dreamed big.

Contents of this article:

- San José, historic city of luxury

- The distinction of the house on a pedestal

- Inception of brick and French bahereque

- “Chic” luxurious homes in 1900’s San José

- Beauty is in the detail

- Modern Architecture in early 1900s

- Casa Museo, witness of the past

- ChepeCletas – the essence of San José

- Video and photography of San José 1800-1900

- Andres Fernandez – 1900

House of Cleto Gonzales Viquez in San José. (photo archive Andrés Fernandez)

San José, historic city of luxury

San José is a city to enjoy, to explore on foot and admire each street corner that harbors historic neighborhoods. Old architecture that still exists in the capital reveals a memorable past, where high society left a clear legacy of their lifestyle. Costa Rica’s elite a little over a hundred years ago reaped the fruits of the land and based their economy primarily on coffee and other agricultural goods. Yet, they lived with a vision far beyond their geographic location, demonstrated in 1884 when San José became the second city in the Americas to have public city lights with electricity, preceded only by the city of New York.

When we examine the city’s past, specifically between 1850 and 1890, it’s clear that this was a time of significant change for the city of San José, driven primarily by the thrust and development of society and economy.

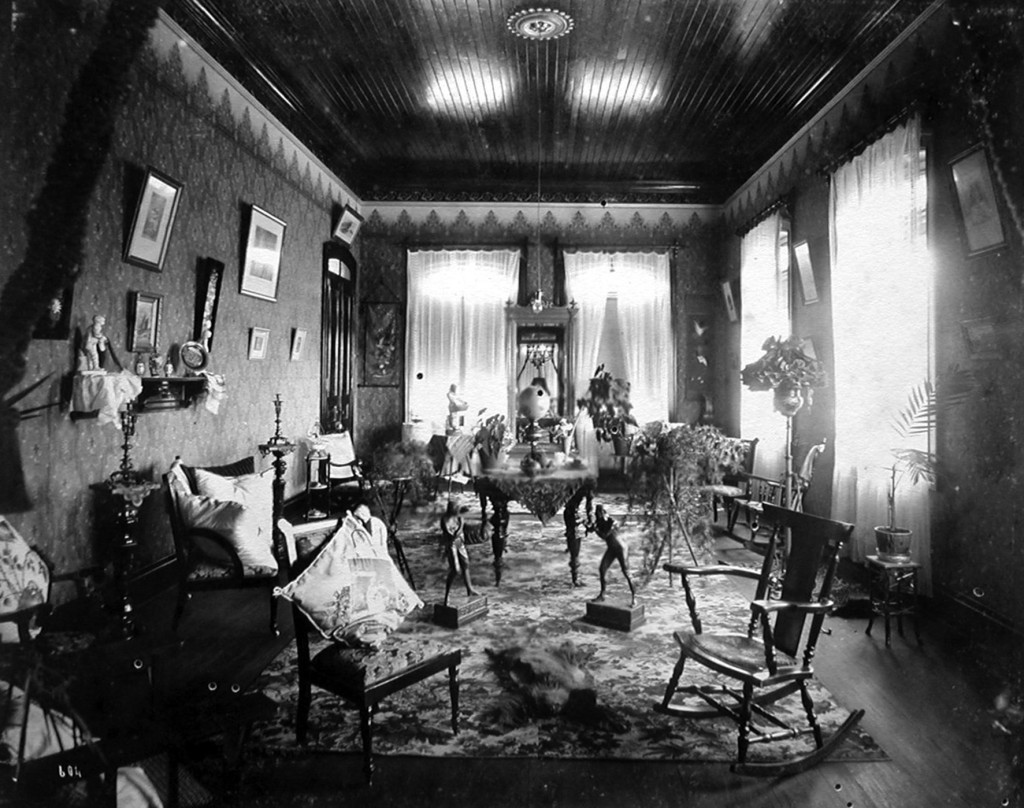

With the increased prosperity of wealthy families in San José, consumption patterns began to change, tastes were refined and households were transformed. The European influence was clear. Luxury in San José city homes took on a different air with new details like the household piano, which the ladies of the house would learn to play taught by a French or Italian teachers who resided in the capital and also taught their native language.

Until this time, wealthy Costa Rican families lived in colonial style homes whose main characteristic was a construction built immediately adjacent to the sidewalk and whose first room worked as a room for receiving visitors. It was a “non-intimate” area of the home where furniture was added to a meeting space.

A bourgeois living room. Residence of Mr. José Castillo Zeledón.(photo archive Architect Andrés Fernandez)

In the local architecture significant change occurred around 1890, driven by the construction of the Atlantic Railway. With the new rail line, imports became much more straightforward and faster. The change made it possible for upper class Josefinos of the era to acquire imported goods like household furniture and new construction materials which became essential detail for San José architecture to take a new turn.

Andrés Fernández, historical architect, researcher and Costa Rican essayist explains that the individuals who really changed Costa Rica’s architecture were Italian Francesco Tenca who arrived in 1896 and Costa Rican Jaime Carranza who arrived in 1900. With their arrival, the two seeded the European architectural models still visible in San José today.

“These architects are in essence what summarizes the architecture of the period. They exemplify the small group that implanted ideas of grand luxury homes in the imagination of Costa Rica’s upper-class. The grand home concept they introduced brought with it beautiful construction in architectural terms and distribution of space. With them were other key elements that even transformed the urban skyline of San José, most importantly the “antejardín” (front garden)” he says.

Fernández adds “Unlike the colonial house that was built right up to the sidewalk, after 1890 the frontal view of these homes changed to a low wall, the gate, the front yard and then the residence.” This type of construction was first visible in the elite city neighborhood near Barrio de El Carmen, which included the area surrounding the church of El Carmen and extended all the way to Parque Morazán. This was the area where most coffee-growers (cafetaleros) lived and where they built the first grand San José homes.

The home of don Cecilio Lindo, on the south side of the Parque Morazán, in barrio del Carmen. (photo archive Andrés Fernandez)

For the architect-historian, Andrés Fernández, an element that marked the constructive change in 1890, in addition to the front garden, was the appearance of what we commonly know as Victorian Architecture. This included elements like the sitting room, dining room, new kitchen areas and a sewing room. “With this architecture a new radically different family model grew, the detached family or Victorian model. This new family model focused on parents and children without necessarily including extended family with grandparents, uncles, etc…”

Fernández goes on to add that “The Victorian house included children’s rooms nad the parent’s bedroom which now had a key. All the puritan victorian tabú was reflected in this architecture, which was initially and without exception a privilege found only amongst the highest social classes.”

The distinction of a “pedestal” home

The architectural work of Francesco Tenca and Jaime Carranza in Costa Rica was part of the eclectic, architectural trend that introduced aesthetic and functional elements of other styles and integrated them into a harmonious whole from the point of view of design. According to Andrés Fernández, Tenca decanted into very well made European models, but not necessarily adapted to the Costa Rican environment, especially from the point of view of climate. “For example, Tenca made a perfect Art Nouveau, as was his Torinese model, but it lacked eaves in a country where it rains almost all year. The house did not function as it should, but from an aesthetic point of view it was a gem. Unfortunately, most of Tenca’s works were lost. What little we know comes mostly from photographic references,” he warns.

On the other hand, the work of Jaime Carranza was analyzed widely, even by a very prominent global architect from that period, Silvio de Vasconcellos. Silvio came to Costa Rica to present a project and was impressed by the quality of Carranza’s architecture, which he called Neoclassical Costa Rican but was really Eclectic with a Neoclassical base.

“The eclecticism that Carranza practiced was as European as Tenca’s, but from a functional point of view he included several conditions that were present in the colonial architecture but not in the Victorian styles. He incorporated the central patio and grand corridor, what the Ticos call ‘el corredor volado’, “he says.

Fernandez mentions that what Carranza did was take the central patio and grand corridor to make them a structural anchor for residential architecture. Moreover, he elevated the homes on a pedestal which worked very well to avoid the natural humidity of San José. “The fact that he raised the homes allowed for hardwood floors that were kept safe from moisture for longer periods. He achieved ventilation above and below which also resulted in elegance. The added buffer from the front yard and the raised height of the house became a social statement, a hallmark of high-class properties and ancestry,” he explains.

“Carranza’s architecture also highlighted the roofs with steep slopes, significant eaves that responded to climactic needs, pediments and columns“.

For Andrés Fernández, Jaime Carranza was the single most important architect of the early twentieth century in Costa Rica. He was directly responsible for the most elegant and extraordinary residences of that period.

“The details of (Carranza’s) architecture are taken from the Neocolassical nad Victorian architectural essence. That combination of two European architectural styles, Mediterranean and Nordic, resulted in an ‘eclectic creole’ style that turned his homes into unique samples. His were the first to transform the mentality of San Jose’s coffee oligarchy and the bourgeois linked to trade. That model of ‘my home’, ie, the space where I see the city and from where the city sees me and my economic power and wealth,” states Fernandez.

“Carranza took an element that the inhabitants of San José already knew and used, the small inner garden, and magnified it. The house of the current Calderón Guardia Museum is a good example and still retains these majestic features. The property was built with a technique called “French Bahareque”, introduced to the local scene by the same architect.”

The Casa Museo Calderón Guardia (photo FB)

Inception of brick and French bahereque

Between 1890 and 1910 brick masonry technology appeared in San José and created a gradual decline in the use of traditional adobe, at least in regard to the construction of large residences. Elsewhere though, popular and rural sector homes continued building with the more conventional technique.

Conventional adobe was difficult to build with, expensive and laborious. The technique was initially abandoned in the 1850s when Bishop Monsignor Anselmo Llorente and La Fuente, who knew mechanical arts, founded the first brickyard. He introduced the technology in Costa Rica and by 1890, when the neighborhood of Amón was forming (founded by Amon Fasileau Duplantier), many houses in the area were built with this new material.

According to Fernandez, “The appearance of brick lead to a change in colonial tradition through the adoption of technological innovation that architecturally spoke of ‘a better economic status’. This also required a more refined labor intensive than the usual neighborhood mason“. While such architectural and urban developments were underway, and after the passing of Francesco Tenca in 1908, an event occurred that radically changed the landscape and life in the capital: the earthquake in Cartago in 1910. The event literally collapsed the provincial capital of Cartago whose houses were mostly made of adobe clay.

La casa de don Alejo Aguilar Bolandi, barrio de Amón. (foto archivo Arq. Andrés Fernandez)

Andrés Fernández mentions “after the earthquake, building with adobe was forbidden. It was deemed an unsafe technology. After the incident inspectors Jaime Luis Carranza and Llach, a Catalan architect residing in the country, were appointed to review the damage. This allowed both professionals to understand the effects of earthquakes on existing structures and resulted in a fundamental disruption in construction methodology in Costa Rica”.

Besides brick, builders in Costa Rica also began using a technique that held a similarity to that of colonial origin and was called French bahareque. It consisted of a wooden structure but not covered in weeds and mud, but rather lined with wire and plastered concrete, representing one of the safest techniques to build “earthquake-proof homes” as they were called at the time.” French bahareque was widely used in architecture and construction from 1910 onwards” he says.

From that year forward two important events occurred in the city of San Jose, one was the urban implosion and the second the popularity of wooden homes, for sale or rent, which did not really exist until that point in time. The city grew enormously after the earthquake because many people in the suburbs of Cartago decided to move and live in San José. This movement generated greater demand for homes which in turn led to the expansion or construction of the first San José neighborhoods for the middle and lower classes, usually consisting of small wooden houses.

“Chic” small luxurious homes in San José 1900

According to Andrés Fernández, in 1910 an emerging social class began to appear, a class that could afford homes with a certain degree of luxury in detail, but not in size. “Thus emerged some beautiful properties with frontal widths of eight to ten meters, designed by Carranza,” he says.

Jaime Carranza, besides having made significant technological contributions to Costa Rica’s architecture and building the homes of many families of lineage or economic power, also dabbled in trade. He dedicated part of his efforts to importing construction materials that opened the market for those smaller homes, for a reduced middle class that was on the rise.

“ Luis Llach also built such houses, small buildings and with a decorated floor only in the corridor and in the hall. The floors of the rest of the house were made of wood. Although these bathrooms did have tile, the tiles only reached a certain height. These homes had a designed the front entrance, but internal construction had a simple creole design. It was an emerging middle class made up mostly of professionals and pharmacists, lawyers, etc.,” he warns.

He adds: “Some of the places where these small but chic and luxurious houses were built, where Carranza y Llach left their mark, were La Soledad, El Carmen expanded all the way to Amón, Barrio Otoya, the access road to Cartago at least until Los Yoses and Central Avenue to La Sabana, which was later renamed Paseo Colón.”

Beauty is in the details

In the 1920s and 1930s the Neocolonial Hispanic architecture began to take over, though Jaime Carranza was not a part of it since he passed in 1930. In this architectural era, Luis Llach continued to lead the way as the first national architects began to appear: Teodorico Quirós Alvarado and José Francisco Salazar. The first neocolonial house was built in 1917 and houses the Chancery or “Casa Amarilla” as it is known to Costa Ricans. Neocolonial homes became the new trend for large residences in San José.

Recent picture of the Chancery or “Casa Amarilla” in San José, Costa Rica. (photo: Dwight Avaloz)

That architecture reminiscent of colonial times appeared after the Mexican Revolution and extended from California and Miami to the south of the continent. Fernandez explains that “ this architecture was full of small arches, tiles, glass and textures that based on colonial Mexico, Peru and the Kingdom of Guatemala, but not in Costa Rica. Though it had nothing to do with us Costa Ricans, the detail is a rich heritage for us because it involved significant forging and woodworking developed by Costa Rican blacksmiths and carpenters,” he says.

“There, luxury was in the detailing of the wood, ceilings, doors, floors, railings and window frames, lamps, and grilles. A window or door from that time is very sensual. Small glass, porcelain knobs or the handrails were all breathtakingly beautiful” proclaims Fernández.

For Andrés Fernandez, these luxury homes also shown in the great outdoors, since “ the rooms were spacious. Not well-lit like we would expect today, but at that time this was sufficient. Other details that revealed luxury were the ceramics which were plated in certain areas, especially the bathrooms ,” he adds.

He goes on to explain that: “In almost all these neocolonial homes there was a saint or a virgin placed in the gardens, patios or corridors. Moreover, the figure of Don Quixote became a prominent iconic image of that enlarged hispanic heritage that was abundant in architectural form.”

The Neocolonial Hispanic American architecture in the 1940s belonged to the upper classes in Costa Rica. It developed on the western side of San José, in Paseo Colón and towards La California and, above all, in the neighborhood of Escalante, which was where many large families settled and is now by far the neighborhood of excellence for neocolonial San José.

Modern Architecture in San José

In 1928 the city of San José began road paving. The contract was awarded to the German firm Weiss und Freitag, which in 1929 brought the engineer and architect Paul Ehrenberg to Costa Rica. He introduced modern architecture in Costa Rica with the first two variables: rational functionalism and art-deco.

However, Fernandez mentions, “rational functionalism is so rational with its pure volumes, large windows, and flat roofs that it was very abstract and difficult to assimilate for Costa Ricans, as was the case in most of Latin America. A good example of this type of construction is the Cubero Otoya residence built in Otoya in 1933,” he says.

The house occupied by the United States Legion in San José, barrio Otoya. (photo archive Andrés Fernandez)

Fernandez explains that with art-deco, the trend followed throughout the globe. “Since it was a style used by the middle class, the upper classes did not incorporate it into their buildings and continued to make their homes in a neocolonial style. Thus, art-deco was for the emerging professional middle classes that did not live in elite neighborhoods. It became ‘popular’,” he warns.

The civil war of 1948 left behind the architectural language of the middle and upper classes, ie, the neocolonial and art-deco, to make way for Modern Architecture referred to as International Style. Thus were born the largest residences in Los Yoses, where in addition to architectural change there was also a major change in the lifestyle of its inhabitants.

According to the chronicler, social clubs in the early twentieth century that were located primarily in the center of downtown, began to move outwards. Those places were not only for billiards, drinking whiskey, reading newspapers and doing business, but now also for more expansive recreation such as playing tennis and golf. That is, the way socialization took place in San José began to change.

“Los Yoses was a suburb in the traditional north american sense, both from an urbanistic point of view in the distribution of streets and spaces, and from a social movement point of view where weekends the neighborhood seemed empty as families enjoyed their leisure time at the clubs. Very few homes had a swimming pool, but it wasn’t necessary because they had one available at the club”, indicates Fernández.

“As for the design of these homes and the way they received guests, the changes included vestibules with closets for coats and guest bathrooms, as well as a bar in the hallway or near to the terrace. The drinks were taken outside in summer or, in winter, inside which also gave way to the appearance of the fireplace. The size of garages began to be double at this time with the change in lifestyle, including the first Auto Mercado supermarket which was in Los Yoses. It was the 50s and the Victorian life had changed … a new tipping point for the lifestyles of Costa Rican urban areas and affluent families””, concludes Fernández.

Casa Museo, witness of the past

Today, San José still hosts architectural beauties of the past that we often see from its external walls without imagining the history stored inside.

Casa Museo in San José, calle 7 and avenida 7.

One such place is Casa Museo. A property built in the early twentieth century by the Gurdian Agüero family and located in the heart of Barrio Amon. Mireya Guardian Varona, pioneer of women’s education and outstanding painter, lived there with her husband for decades. In 1964 she decided to remodel the family home, with the idea of building an urban work to beautify San Jose.

Clari Vega, Co-founder of LX Costa Rica and the country’s premiere luxury real estate agent, states “Many customers looking for luxury properties in San José appreciate the historical detail of these buildings. Despite the appeal of contemporary design, they share a passion to combine the periods and elements, recognizing that everything in our present has a past. We’ve seen a revival in these historic neighborhoods, with new property owners who drive the architectural renovation without overthrowing the past.”

The Casa Museum remodeling process resulted in substantial changes to the original facade in the front of the house. This remains intact to this day and stands out because it is made of reinforced concrete and brick, and molded to simulate stone finish doors, windows and wrought iron elements. It is considered a property of eclectic or “mestizo” style characterized by varied finishing styles in the interior, including Neoclassical and English, French and even Aztec influence.

Casa Museo 707 in downtown San José, glowing in tradition and a renovated air.(photo: Dwight Avaloz)

The house was abandoned for eleven years. In 2011 it was rescued by the Belgian couple composed of Jean-Marc Steylemans, interior architect and designer, and Nathalie Robin, robotics and automation engineer and painter, artist and decorator. The couple currently lives there with their three daughters, on the extended property of 700 square meters, with eight bedrooms, eight bathrooms and several rooms, now fully restored thanks to their own efforts.

According to Jean Marc Steylemans, “ before restoring we took one significant historical research with period photographs and the remains found at the site. Beneath the walls and using a special paint remover we imported from Germany we found the original walls, details and the colors of the original decoration,” explains the current owner of the property.

“Then we started with the removal phase. We found flooring above the original, covered windows, gypsum on walls, ceilings overlapped with the old, high humidity, even house doors from early last century were found in the basement, which we returned to their original place. After that, we started the restoration phase that lasted about two years, which resulted in the image that you see today in the renovated interiors,” he says.

Jean-Marc Steylemans explains that the idea of calling the property “Casa Museo” was because the home originally belonged to a painter, and both Steylemans and his wife wanted to keep that spirit alive.”With this in mind we took on artwork from Costa Rican artists to display on the walls. This allows us to eventually conduct private tours and cultural events which take advantage of the magnificent history and visual storytelling of this former residence.”

To Steylemans this is a house that has a very special personality. “The original owner, Mireya Guardian, filled this home with her love, interests and passion for art. We did the same during the restoration process,” he concluded.

ChepeCletas, the essence of enjoying San José

Despite the modernism and growth of the capital, many josefinos value the cultural heritage of the city and promote it. One of these is Roberto Guzman, a staunch admirer of San Jose and founder of the movement “ChepeCletas“, an innovative initiative that uses cycling or evening walks to motivate the inhabitants of the city and suburbs to take ownership of urban spaces and see the city in a different light.

Guzmán continues to be impressed by how a simple little town, besides being one of the first cities in the world with electric lighting, “also decided to invest in education, the transformation of public space and the creation of first order cultural spaces like the National Theatre completed in 1897.”

“Many large infrastructure elements of San José that are still around were built in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These include the first hydroelectric plant, the water tanks in Barrio Aranjuez, the old customs building, the Colegio de Señoritas and the Buenaventura Corrales School, the Central Park, National Park, Park of Spain and Morazán Park, among many others“, he adds.

For Roberto Guzmán, living with the past nowadays is a complicated relationship, “ on the one hand this legacy gives identity to the city and in many cases is a source of national pride, but on the other hand it is increasingly scarce due to indifference and disinterest which allows for valuable historic buildings to deteriorate. In some cases they are converted into parking or demolished to make room for other buildings,” says the catalyst of this urban movement that increasingly attracts more people.

Find out more about Chepecletas on Facebook: www.facebook.com/ChepeCletasCR

Video and photography of San José in the early 1900s

Video by Yamileth Cernas. A beautiful and emotional journey through time. Pictures of San Jose, Costa Rica in the years 1900-1940. The first two images are the oldest, the first mid-nineteenth century and the second is from the late nineteenth century.

About Andrés Fernandez, architectural chronicler of San José

Architect, researcher and chronicler of the city. Andrés Fernandez has written on such topics as art, architecture, urbanism and culture in Costa Rica in collaboration with Áncora magazine in the national newspaper La Nación, Su Casa magazine from La Nación, Nacional de la Cultura from EUNED, Habitar from the National College of Architects, Herencia from the UCR, and AmbienTico from the UNA.

Regarding historic architecture, Andrés Fernandez has published books including: Un país, tres arquitecturas. Art nouveau, Neocolonial Hispanoamericano y Art Decó en Costa Rica 1900-1950 (Editorial Tecnológica, 2003); Imaginario. Un itinerario josefino junto a la pintora Virginia Vargas (Editorial Costa Rica, 2004); Barrio México Art-Decó. Un barrio josefino de 1930-1950 (from the Revista Herencia, 2006); Los muros cuentan. Crónicas sobre arquitectura histórica josefina (Editorial Costa Rica, 2013) and Punto y contrapunto. La Plaza de la Cultura (Museos del Banco Central de Costa Rica). In additiona, he has several projects ongoing including Pasado construido. Crónicas sobre arquitectura histórica josefina II and Continuidad y cambio. Arquitecturas modernas en Costa Rica.

Andrés was also one of the researchers of the Guide to Architecture and Landscapes of Costa Rica (Junta de Andalucía / Association of Engineers and Architects of Costa Rica, 2011) and is the Chair of Critical History of architecture in Costa Rica in U Véritas.